A quick refresher on the long tail

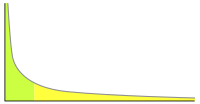

I'm sure you've heard of the long tail, right? It's the probabilistic distribution pattern characterized by a "big head," or large cluster of results at the beginning, which quickly declines into a "long tail". The neat thing about a long tail distribution is that even though the tail part may seem small, it can extend out so far that the number of results in the tail-end typically exceeds the number in the much larger-looking head end. As usual, Wikipedia does a good job of illustrating this:

In this graph, the areas of both the green "head" end and yellow "tail" end are equal. However, the tail may extend out a considerable ways, and thus could potentially be much, much larger.

The long tail was most famously used to describe the business practices of companies like Amazon and Netflix when they first began. Unlike their brick-and-mortar counterparts (e.g. Barnes and Noble and Blockbuster Video), both companies didn't have to own, operate and maintain real-world retail presences. They were (and are) just giant warehouses with fancy e-commerce front ends. So while Barnes and Noble and Blockbuster have limited retail space to work with and can thus only stock a limited number of items, Amazon and Netflix don't effectively have that barrier. Consequently, they can maintain much, much larger inventories pretty cheaply. At the same time, their business models allow for selling both large quantities of popular "big head" items (where they compete against their brick-and-mortar counterparts), but also small quantities of a very large group of less popular items (where they effectively have no brick-and-mortar competitors, because nobody could afford to stock so many unique items in a retail space).

What on earth does any of this have to do with digital signage?

In a nutshell, it appears that the historical digital signage adoption rate has been driven largely by price. Mapping the price trends from our digital signage pricing articles against the data from our meta-analysis of digital signage market size reveals a pretty clear relationship:

So, as prices go down, we see more screens deployed. That makes sense, right? Right. The interesting thing is that for most deployments, the costs are spread out in a long tail fashion. Take a look at any of our previous pricing guides and you'll see the "big head" where the initial capex takes place (notably, buying the screen, media player, etc. and getting it all installed). But there's a long tail portion after that, consisting of creating content, doing the scheduling, handling maintenance tasks and the like. Our most recent data illustrates that on a month-to-month basis, operating expenses are over six times the size of amortized capital expenses. Even going back to the 2010 data (which suggested more modest staffing requirements), opex was about four times the size of amortized capex. And the longer a network runs, the larger its long tail costs are (but this is true for nearly any operating business, of course).

All of this furthers the point we tried to make a few weeks ago in our post about front-loaded scale. In that article, we came to the conclusion that most of the networks that have failed probably did so because entrepreneur and funding source alike misunderstood the true funding requirements of the network -- and more importantly, how those requirements scale up with network growth. You see, the cost of operating a network never goes away, but as we saw in that article, it also doesn't scale linearly with network size. So while running a 100 screen DOOH network might cost $X, running a 1,000 screen network isn't going to cost $10X -- it will probably be more like $2-5X. However, the 1,000 screen network has far better odds of succeeding because of how the larger scale affects ad sales, as described in our earlier article.

The moral of the story is this: If you're planning to fund or operate a network, allocate more funding for operations than for capital expenses. Failing to do so seems to be a pretty great way of assuring your network's demise.

Subscribe to the Digital Signage Insider RSS feed

Subscribe to the Digital Signage Insider RSS feed

Comments

RSS feed for comments to this post